Overview

Women at the Center of Change

Across Africa’s wild landscapes—from Kenya’s sweeping conservancies to South Africa’s fragile water-source areas—women remain the backbone of their communities. They are farmers, entrepreneurs, rangers, and caregivers, maintaining the delicate balance between people and nature. Yet their influence in conservation and tourism has long been limited by structural inequities, restricted access to resources, and patriarchal norms.

The African Nature-Based Tourism Platform, supported by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and WWF, set out to change that. When COVID-19 shuttered global travel and tourism, the ripple effects threatened community livelihoods and the funding that supports conservation. Rural nature-based tourism enterprises—such as lodges, craft businesses, guiding services, and community conservancies—were hit particularly hard. Many women, whose roles in these economies were already precarious, became even more economically vulnerable.

The Platform was developed in response to this crisis, serving as a bridge between donors and local communities that had lost their livelihoods. Its bottom-up strategy involved collecting data, highlighting local needs, building capacity, and catalyzing funding for those most affected by the pandemic. From the start, its architects recognized a deeper truth: rebuilding nature-based economies sustainably required placing women not on the margins, but at the center.

Structured Inclusion

As the project partnered with local organizations in Botswana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe to conduct surveys and assess COVID-19’s impact on communities and small to medium enterprises (SMEs) within the nature-based tourism sector, stories from women revealed a shared experience of loss and resilience.

In Zimbabwe, a lodge housekeeper Rose Tshuma lost her salary and was forced to forage for wild fruits to feed her family. “We’re all hungry,” she said. In Zambia, wildlife officer turned conservation research technician Anety Milimo noted women were often the first to lose incomes from “nonessential” tourism work. “Women in the community were desperate,” she said. “Some people moved into protected areas to get wood … we lacked the resources to help.” In Kenya, Loiman Letolo, who earned income by selling beaded jewelry to safari-goers at the entrance to Maasai Mara National Reserve, explained: “I’ve been selling at the roadside since I was a teenager. There have always been tourists. Now there are no tourists, there is no dollar, and there is no food.”

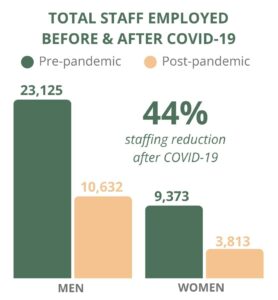

In total, the Platform conducted 687 surveys with SMEs across the region. Its Data to Impact report revealed how gender-disaggregated data offered nuanced insights into how men and women were differently affected by the pandemic. Of those surveyed, 23,125 men and 10,632 women were employed in the nature-based tourism sector before COVID-19. Afterwards, these numbers dropped to 9,373 men and 3,813 women. Recognizing that these realities were not side stories but central to recovery, the Platform’s Gender Action Plan became the backbone of a continent-wide strategy to ensure women were not only participants but leaders in Africa’s post-COVID-19 nature-based tourism revival.

In total, the Platform conducted 687 surveys with SMEs across the region. Its Data to Impact report revealed how gender-disaggregated data offered nuanced insights into how men and women were differently affected by the pandemic. Of those surveyed, 23,125 men and 10,632 women were employed in the nature-based tourism sector before COVID-19. Afterwards, these numbers dropped to 9,373 men and 3,813 women. Recognizing that these realities were not side stories but central to recovery, the Platform’s Gender Action Plan became the backbone of a continent-wide strategy to ensure women were not only participants but leaders in Africa’s post-COVID-19 nature-based tourism revival.

“We don’t just ask partners to consider gender,” said WWF’s Nikhil Advani, who leads the Platform. “We look for those creating pathways where gender inclusion is not optional but the foundation for sustainability.”

Building Gender Equity into the Blueprint

From the earliest funding stages, all partners had to demonstrate how their projects integrated gender equity and social inclusion. The Platform prioritized those showing clear commitments to gender inclusion for support. Then, insights from data and vulnerability assessments informed the development of community-led projects designed to promote inclusion and empower women.

From the earliest funding stages, all partners had to demonstrate how their projects integrated gender equity and social inclusion. The Platform prioritized those showing clear commitments to gender inclusion for support. Then, insights from data and vulnerability assessments informed the development of community-led projects designed to promote inclusion and empower women.

In Kenya, the Platform worked with the Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association (KWCA). “For the longest time, conservation has been lopsided toward men,” said Vincent Oluoch of KWCA. “We work to ensure women not only participate but own and manage enterprises and secure fair funding.”

With ANBTP support, KWCA worked in Lumo Conservancy, where women had long been marginalized in governance. Community liaison officer Purity Manyatta noted that “women’s voices were often not taken seriously.” Through site-level assessments, KWCA formed a women-and-youth forum to influence key decisions. Oza Ranch, a conservancy member, lowered its membership fee from 2,800 to 300 Kenyan shillings to increase women’s access. As a result, four women were elected to conservancy boards—an important step toward fulfilling Kenya’s Community Land Act of 2016, which requires at least one-third female representation. In total, KWCA targeted 7,000 beneficiaries in the Lumo Conservancy to address governance challenges, including gender and youth bias. “Patriarchal systems of governance remain the biggest hurdle for women, especially in land ownership,” said KWCA’s Joyce Mataru.

In South Africa, the Platform supported Nourish, a nonprofit working near Kruger National Park, to expand its craft enterprise hub. The hub trains artisans in indigenous crafts and facilitates market access for women and other marginalized groups, particularly those facing barriers to entering the tourism value chain.

Also in South Africa, WWF worked with Environmental & Rural Solutions, which is not only women-founded but also women-led. Here, women and youth were trained in climate-smart agriculture—from mulching and composting to cultivating indigenous crops that withstand erratic rainfall. “Women are the reason people survive in rural areas,” said co-founder Nicky McLeod.

ERS has partnered with WWF over the years in its mission to support sustainable land management, biodiversity conservation, and climate resilience in South Africa’s rural landscapes. It works with local communities, integrating traditional ecological knowledge with scientific practices to restore ecosystems and secure rural livelihoods. Women feature prominently in ERS’s approach because they are often the primary caregivers, food producers, and water stewards in their households and communities.

This approach is fully aligned with the African Nature-Based Tourism Platform (ANBTP), which recognizes that women often carry the burden of climate shocks—managing household nutrition, water, firewood, and community welfare. By strengthening women’s economic standing and voice within local institutions, the Platform helps buffer communities against future shocks like droughts, market disruptions or another pandemic.

In Botswana, for example, the Platform supported a horticulture project implemented by local NGOs to help communities—especially women—move into nature-positive agriculture linked to tourism and local value chains. Known as the OKACOM Project, the initiative worked with 30 farmers—18 of them women—in the Cubango-Okavango River Basin. It addressed food insecurity and socio-economic vulnerability.

“In Botswana, where food and water security emerged as top concerns during the pandemic, nearly half of the alternative income-generating ideas raised by respondents were agricultural,” said Advani. “By linking agriculture and local ecotourism, women’s enterprises help reduce pressure on fragile habitats.”

“In Botswana, where food and water security emerged as top concerns during the pandemic, nearly half of the alternative income-generating ideas raised by respondents were agricultural,” said Advani. “By linking agriculture and local ecotourism, women’s enterprises help reduce pressure on fragile habitats.”

In Namibia’s Zambezi region, WWF implemented alternative nature-friendly livelihood initiatives as part of climate adaptation projects. These initiatives included training youth and women in beekeeping and basket weaving, as well as providing market access for their products.

Skills, Visibility, and Voice

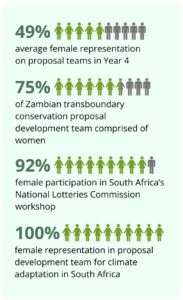

To strengthen gender integration across its portfolio, ANBTP hosted a proposal-writing workshop with a strong focus on gender and social inclusion. Participants assessed where their projects fell along a “gender continuum”—from neutral to transformative—and addressed intersectionality across race, education, ability, and language.

The Platform also championed female visibility on the international stage. During Climate Week NYC 2024, ANBTP ensured gender balance among its six partner representatives. At the Nest Climate Campus panel, half the speakers were women.

Most recently, in August 2025, the Platform supported Kenya’s 2nd Conservancies Investment Forum in Nairobi. “It was one of the biggest achievements [of the event] to see people owning up and saying women are equally as good as men in leadership and natural resource management,” said Maurine Nduati, Partnership Engagement and Gender Officer at the Taita Taveta Wildlife Conservancies Association.

She noted that in Taita Taveta, four women were recently elected to the board of a conservancy that had no female leaders since the 1970s. Her example reflected a broader shift echoed throughout the forum, where conservancy leaders, investors, government officials and community voices gathered to spotlight the people shaping Kenya’s conservation future — with women more prominent than ever before.

She noted that in Taita Taveta, four women were recently elected to the board of a conservancy that had no female leaders since the 1970s. Her example reflected a broader shift echoed throughout the forum, where conservancy leaders, investors, government officials and community voices gathered to spotlight the people shaping Kenya’s conservation future — with women more prominent than ever before.

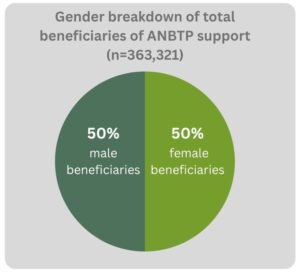

By the end of Year 4, ANBTP-supported initiatives reached 363,321 direct beneficiaries, including 183,292 women who explored new livelihood opportunities, and grew in agency and skills.

Lessons for the Future

Advani notes that the ANBTP’s data-driven and inclusive design underscores several key lessons. “Women’s exclusion undermines conservation. When women lack access to decision-making, land rights, or resources, conservation outcomes suffer.”

Through its structured gender approach—grounded in policy reform, leadership opportunities, and measurable outcomes—the African Nature-Based Tourism Platform is redefining inclusive conservation. By elevating women’s voices, ensuring they lead in governance, and embedding gender into every phase of project design, the Platform has proven that the path to sustainable tourism is fundamentally a path toward equity.

“The goal,” said Sylvia Looseyia of The Maa Trust in Kenya, “is for women to have ownership—where they no longer feel the need to shrink themselves or seek permission from somebody else to do something.”

Written by Dianne Tipping-Woods

Zimbabwean-born journalist Dianne Tipping-Woods has spent most of her freelance career looking for stories in southern Africa where travel, conservation and development intersect. She is now based in a nature reserve close to the Kruger National Park in South Africa.

October 2025